- Home

- Bill Pronzini

The Snatch - [Nameless Detective 01] Page 19

The Snatch - [Nameless Detective 01] Read online

Page 19

“Three hundred thousand dollars,” I said half audibly. “The price of a soul.”

“I’m a murderer,” he said, “yes, I’m a murderer, I killed him don’t you know that? I murdered him murdered him murdered him . . .”

He kept on that way, softer and softer, the words becoming unintelligible to me, and he was speaking only to himself now, to the very essence of his being. He no longer knew I was there. He was a callous man, a hard man, a man who had been very close to crime, even to criminals, over the years, skirting the periphery of illegality and immorality, never really affected by it—and yet, he had never himself had to deal with the cold, terrifying fact of death, of murder, of the awesomeness of snuffing out a human life. Faced with the thing he had done, the circumstances which had led to the act—examining it within himself—he was unable to cope with it; it was destroying him „ so quickly and so completely that the effects of that destruction were outwardly visible.

As I listened to him babbling, I realized that he was totally incapable of pulling that trigger another time, of taking a second human life—and I realized, too, that I had known all along that this was true, that I had stood facing his gun not as a brave man facing death, but as a man who knows irrevocably the outcome of a situation, knows that he will not be harmed in any way. I looked deep into Martinetti’s eyes and saw the terrible guilt, the cancerous insanity burning in their depths, and then I forced my gaze again to the gun in his hand. It was no longer pointing at me; the muzzle was angled toward the floor at my feet.

There were perhaps three steps between us, three long quick strides, and his shoulders were slumped now, muscles lax, mouth open to release his murmurings—three long quick strides. I took them without thinking any more about it and hit him the same way, a long hard right-hand flush on the point of his jaw, the shock of the impact exploding the length of my arm and into my armpit, pain through my knuckles, and he went down clean and silent, with his eyes rolling up in their sockets, sprawling out on top of the gun, covering it with his body, unmoving.

I stood looking down at him, breathing heavily. I felt nothing at all. The anger and the hatred and the disgust were gone now, and they had left nothing in their place but a hollow vacuum, a weariness that transcended the physical.

My hands were trembling and I thrust them into the pockets of my overcoat to still them, and the fingers of my right hand encountered the package of cigarettes I had bought earlier in the evening. I took it out and looked at it, and then I closed my eyes and tore open the pack and lit one and dragged smoke deep into my lungs. It was harsh and raw and hot and brought a vague weakness to my knees—it was fine.

I went over to the telephone and picked up the receiver and stood holding it, looking over at Martinetti lying very still, very old, like some crumbling sarcophagus. And, strangely, I thought then of Erika.

You were right, Erika, I thought. You were right that I’m honest and ethical and sensitive, that I don’t have a lot of flair or even a lot of guts. You were right that I’m not a hero, and that I never will be.

But you were wrong, too. You said that I’m nothing more than a little boy playing at being a detective, that I’m living in the past, in a world that never existed. But the world I live in, you live in, is a world sicker and harsher and crueler than anything in man’s imagination, a lousy world that requires men like Donleavy and Reese and Eberhardt to keep it from becoming sicker and harsher and cruder than it already is, dedicated men, Erika, men who care. I’m one of those men—how or why I got to be that way is of no real consequence—and because I am, I’m not living the lie you think I am.

You can’t change me, Erika, you can’t hope to make me into something that I’m not and never will be. And that’s why, if I must choose, I won’t choose you, even though I love you; I am what I am, and how can you cease being—how can you alter in any way—what you are?

I’m no hero.

I’m just a cop.

I’m just a man.

I sucked deeply, hungrily, on my cigarette and dialed the operator, and when she came on I asked her for the police above the tintinnabulation of the restless and .eternal sea. . . .

Twospot

Twospot Dragonfire

Dragonfire Sentinels

Sentinels The Peaceful Valley Crime Wave

The Peaceful Valley Crime Wave Hardcase

Hardcase Bleeders

Bleeders Demons

Demons The Pillars of Salt Affair

The Pillars of Salt Affair Epitaphs

Epitaphs Spook

Spook Hoodwink

Hoodwink Bug-Eyed Monsters

Bug-Eyed Monsters Endgame--A Nameless Detective Novel

Endgame--A Nameless Detective Novel The Hidden

The Hidden The Paradise Affair

The Paradise Affair Oddments

Oddments Boobytrap

Boobytrap Blue Lonesome

Blue Lonesome Scenarios - A Collection of Nameless Detective Stories

Scenarios - A Collection of Nameless Detective Stories Breakdown

Breakdown Panic!

Panic! The Bags of Tricks Affair

The Bags of Tricks Affair Quicksilver (Nameless Detective)

Quicksilver (Nameless Detective) Hellbox (Nameless Detective)

Hellbox (Nameless Detective) Nightcrawlers nd-30

Nightcrawlers nd-30 Zigzag

Zigzag The Jade Figurine

The Jade Figurine The Stolen Gold Affair

The Stolen Gold Affair The Stalker

The Stalker The Lighthouse

The Lighthouse Fever nd-33

Fever nd-33 Nightshades (Nameless Detective)

Nightshades (Nameless Detective) Scattershot nd-8

Scattershot nd-8 The Hangings

The Hangings Mourners: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Mystery)

Mourners: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Mystery) Graveyard Plots

Graveyard Plots Pumpkin

Pumpkin Schemers nd-34

Schemers nd-34 The Bughouse Affair q-2

The Bughouse Affair q-2 The Other Side of Silence

The Other Side of Silence Savages: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Novels)

Savages: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Novels) Crazybone

Crazybone Schemers: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Novels)

Schemers: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Novels) Gun in Cheek

Gun in Cheek In an Evil Time

In an Evil Time Son of Gun in Cheek

Son of Gun in Cheek Camouflage (Nameless Detective Mysteries)

Camouflage (Nameless Detective Mysteries) Hoodwink nd-7

Hoodwink nd-7 With an Extreme Burning

With an Extreme Burning Vixen

Vixen More Oddments

More Oddments Carmody's Run

Carmody's Run Small Felonies - Fifty Mystery Short Stories

Small Felonies - Fifty Mystery Short Stories Labyrinth (The Nameless Detective)

Labyrinth (The Nameless Detective) Jackpot (Nameless Dectective)

Jackpot (Nameless Dectective) Case File - a Collection of Nameless Detective Stories

Case File - a Collection of Nameless Detective Stories Undercurrent nd-3

Undercurrent nd-3 Betrayers (Nameless Detective Novels)

Betrayers (Nameless Detective Novels) Deadfall (Nameless Detective)

Deadfall (Nameless Detective) Bones nd-14

Bones nd-14 The Snatch nd-1

The Snatch nd-1 Bindlestiff nd-10

Bindlestiff nd-10 Blowback nd-4

Blowback nd-4 A Wasteland of Strangers

A Wasteland of Strangers Double

Double The Bags of Tricks Affair--A Carpenter and Quincannon Mystery

The Bags of Tricks Affair--A Carpenter and Quincannon Mystery Quarry

Quarry Nameless 08 Scattershot

Nameless 08 Scattershot Mourners nd-31

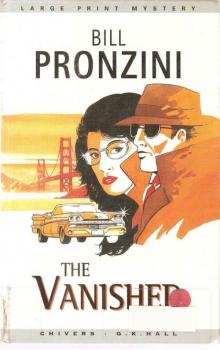

Mourners nd-31 The Vanished

The Vanished Savages nd-32

Savages nd-32 Quincannon jq-1

Quincannon jq-1 Hellbox nd-37

Hellbox nd-37 The Crimes of Jordan Wise

The Crimes of Jordan Wise Bones (The Nameless Detecive)

Bones (The Nameless Detecive) Nothing but the Night

Nothing but the Night Camouflage nd-36

Camouflage nd-36 Pumpkin 1doh-9

Pumpkin 1doh-9 Blowback (The Nameless Detective)

Blowback (The Nameless Detective) Give-A-Damn Jones: A Novel of the West

Give-A-Damn Jones: A Novel of the West Shackles

Shackles The Violated

The Violated Beyond the Grave jq-2

Beyond the Grave jq-2![The Vanished - [Nameless Detective 02] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/the_vanished_-_nameless_detective_02_preview.jpg) The Vanished - [Nameless Detective 02]

The Vanished - [Nameless Detective 02] Quincannon

Quincannon Undercurrent (The Nameless Detective)

Undercurrent (The Nameless Detective) Step to the Graveyard Easy

Step to the Graveyard Easy Nightcrawlers: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Mystery)

Nightcrawlers: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Mystery) The Eye: A Novel of Suspense

The Eye: A Novel of Suspense Betrayers nd-35

Betrayers nd-35 Quicksilver nd-11

Quicksilver nd-11 Acts of Mercy

Acts of Mercy Breakdown nd-18

Breakdown nd-18 Sleuths

Sleuths![The Snatch - [Nameless Detective 01] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/the_snatch_-_nameless_detective_01_preview.jpg) The Snatch - [Nameless Detective 01]

The Snatch - [Nameless Detective 01] Scenarios nd-29

Scenarios nd-29 Nightshades nd-12

Nightshades nd-12 Snowbound

Snowbound Deadfall nd-15

Deadfall nd-15 Bindlestiff (The Nameless Detective)

Bindlestiff (The Nameless Detective) Fever: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Novels)

Fever: A Nameless Detective Novel (Nameless Detective Novels)